Good morning. I'm delighted to be here with you today. Let me begin by thanking the conference organizers and the Waterfront Alliance for inviting me to participate in this conference.

Today, my remarks will focus on the economic health of the Greater New York region during the pandemic. I'll talk about the depth of the downturn, the progress we've made, and our prospects going forward. As always, what I have to say reflects my own views and not necessarily those of the New York Fed or the Federal Reserve System.

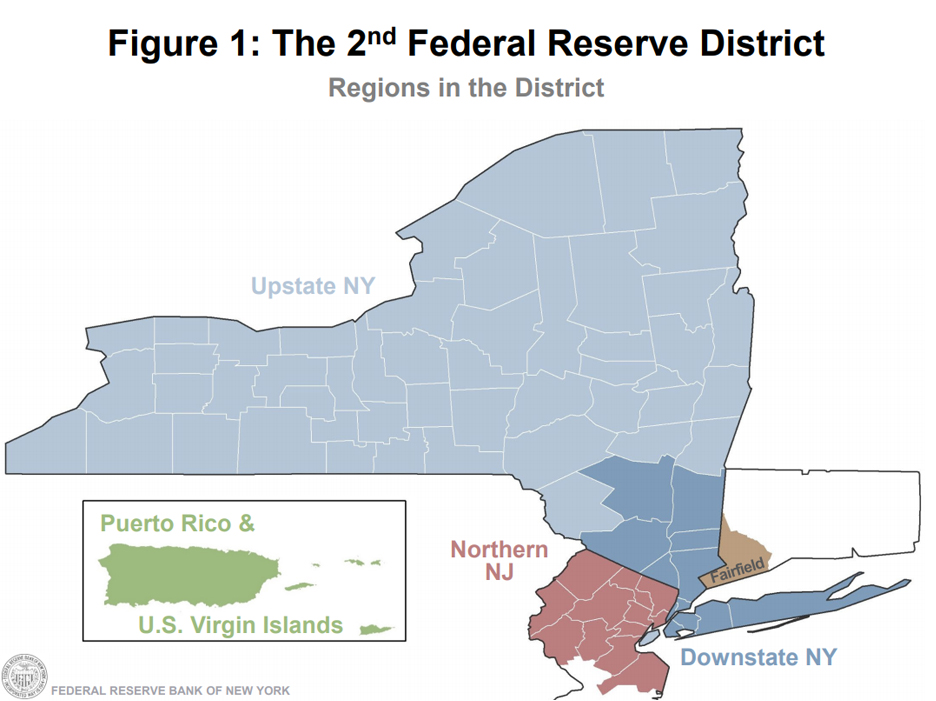

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the structure of the Federal Reserve, it is divided into 12 regional districts across the country, in recognition of the fact that the national economy is really a collection of many different local economies, each with its own unique features. As shown in Figure 1, the New York Fed represents the Second District, which consists of New York State; Northern New Jersey; Fairfield County, Connecticut; Puerto Rico; and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

At the New York Fed, we are deeply committed to serving our region, and this commitment manifests in several ways. Our economists conduct research on issues of importance to the region. We actively monitor the regional economy by analyzing a wide array of data and indicators, and we produce our own business surveys to help track regional economic conditions.1 We assess the financial health of households in our region and across the nation through our Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit. We also think it is very important to hear directly from our stakeholders. We meet regularly with community and business leaders to learn about developments in our region and visit different parts of our district to talk directly with local businesses, nonprofit organizations, community groups, and, importantly, the people who live and work here. This on-the-ground intelligence is extremely valuable and helps shape our view of the regional economy.

I'm particularly pleased to be speaking to supporters of the Waterfront Alliance today. We have a common goal of fostering a resilient economy, and also share concerns about the risks of climate change. At the New York Fed, we have a number of initiatives underway aimed at better understanding the risks that climate change poses to the financial system and the economy more generally. The Federal Reserve has joined a number of international bodies engaged in climate-related work, such as the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), and, more recently, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). In short, we want to be part of the solution to one of the major challenges of our lifetime.

The Regional Economy during the Pandemic

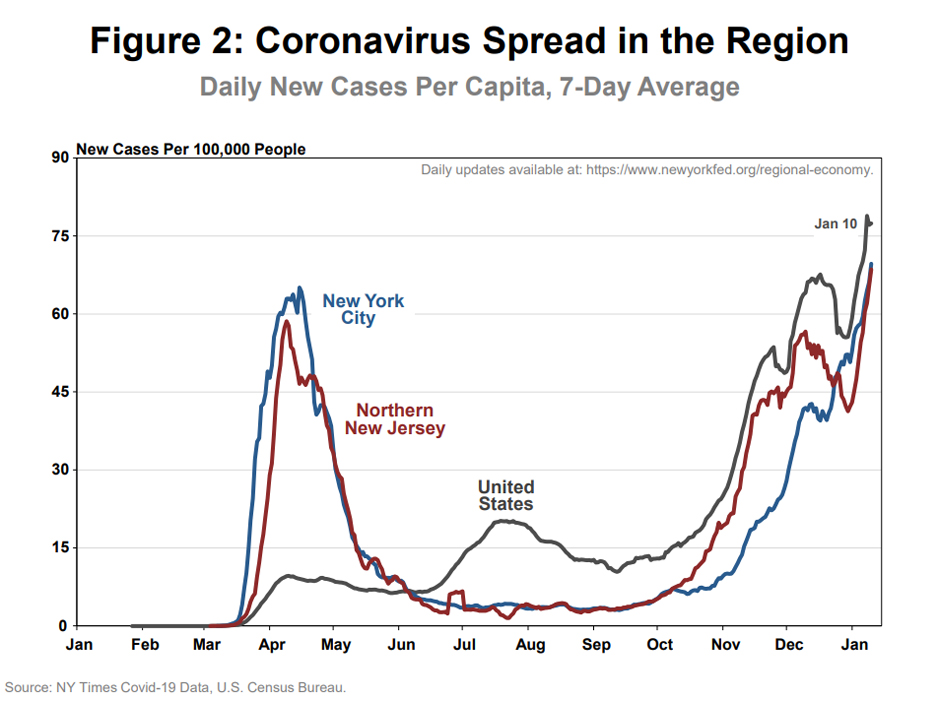

The pandemic remains a serious public health crisis that continues to have important impacts on the global, national, and regional economies. On the regional front, we are all familiar with how hard the New York City area was hit as the pandemic took hold early last year. Figure 2 shows the spread of Covid-19 in New York City and Northern New Jersey compared to the nation. We saw a tremendous spike in cases back in March and April, and even this signficantly understates the spread of the disease given the lack of widespread testing back then. While the area avoided the summer surge experienced in other parts of the country, we have seen a resurgence during this winter wave. With the virus spreading widely again, there is heightened uncertainty among businesses and consumers alike.

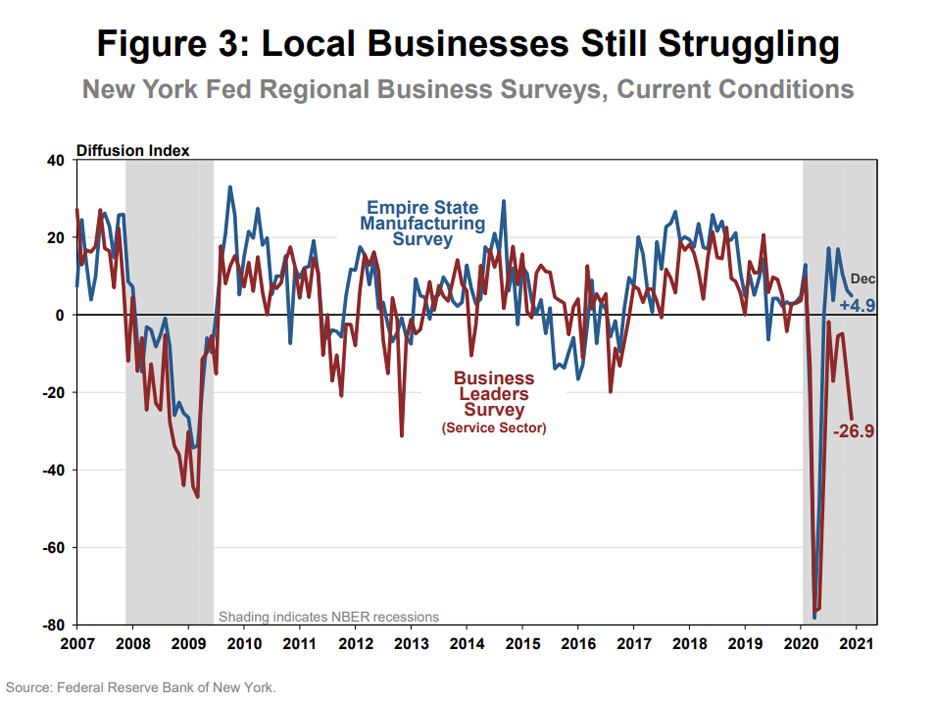

Indeed, the pandemic continues to have severe effects on the regional economy, and it's going to take time to get back to full strength once it subsides. Looking at business activity in the region, Figure 3 shows the headline indexes from our two regional business surveys: the Empire State Manufacturing Survey, which covers manufacturing firms in New York State, and the Business Leaders Survey, which covers service sector firms in the broader New York-Northern New Jersey region. Positive values suggest that activity grew over the month, while negative values signal a decline. As the pandemic took hold, businesses in the region saw an immediate and sharp drop-off in economic activity, as the indexes plunged to historic lows. This drop was followed by some recovery in the region's manufacturing sector, and we can see that the index turned positive, though growth has waned in recent months. The corresponding index for the region's service sector also plunged, and while it also has moved up from its lows, it has yet to turn positive. Notably, the most recent readings from December were particularly weak in both sectors. Manufacturing growth was limited, and service sector activity posted a significant decline, pointing to renewed weakness in the regional economy.

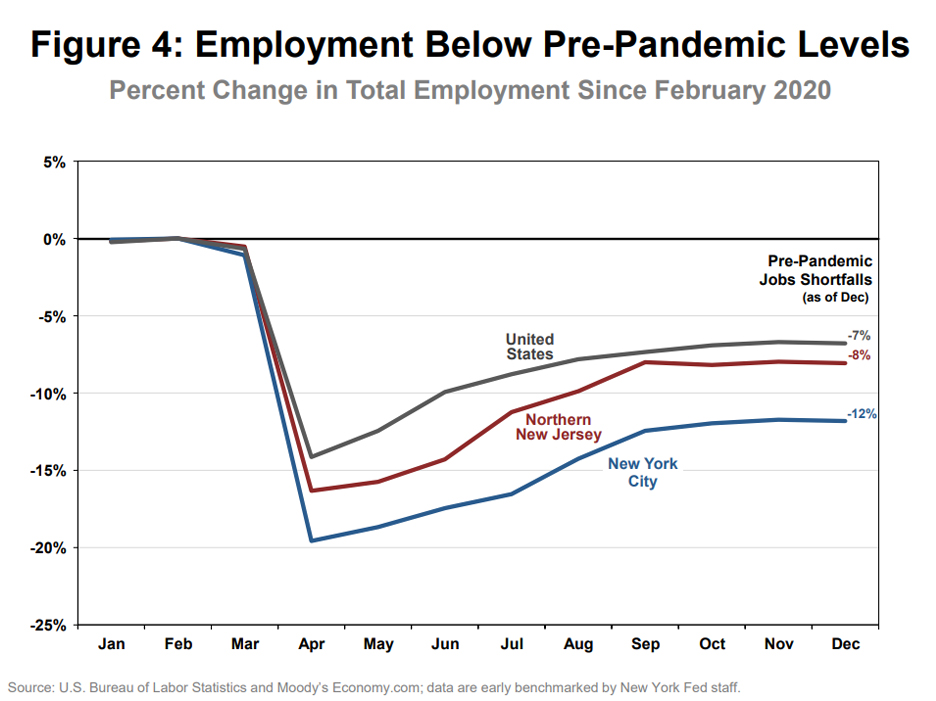

Job losses due to the pandemic have also been unprecedented. As shown in Figure 4, the nation saw employment decline by 15 percent at the onset of the pandemic, compared to 20 percent in New York City and 16 percent in Northern New Jersey. The biggest job losses by far were in the leisure and hospitality industry, followed by the retail sector, and education and health. In contrast to more typical cyclical downturns, job losses were much more muted in the manufacturing sector. Initial job losses bottomed out in April, and since then, a little more than half of the jobs that were lost have been gained back. Last week's jobs report was a disappointment, as it showed employment declined again as 2020 came to a close. The nation's employment is still 7 percent below pre-pandemic levels, while employment in New York City remains a staggering 12 percent lower. Northern New Jersey has a jobs shortfall of 8 percent. Despite substantial progress, there is much left to do, as the remaining job shortfalls in the region are two to three times larger than during the depths of the Great Recession.

As often happens during recessions, some workers were much more likely to lose their jobs than others, particularly the most vulnerable.2 Because this downturn has resulted in such large job losses in leisure and hospitality and retail, it has been particularly hard on the lower-skilled workers who tend to work in these sectors. Analysis by my colleagues at the New York Fed shows that employment for low-wage workers in the region dropped by nearly half at the early stages of the pandemic, while high-wage workers saw little, if any, decline.3 In fact, after growing slightly through the summer months, employment among high-wage workers is now just slightly below where it was before the pandemic hit, while employment among low-wage workers still remains more than 20 percent below pre-pandemic levels.

And, it's not only lower-wage workers who are being affected so adversely. We know that people of color have been affected by Covid-19 at significantly higher rates—and they have been hit harder in the labor market as well, with steeper job losses and more significant job shortfalls.

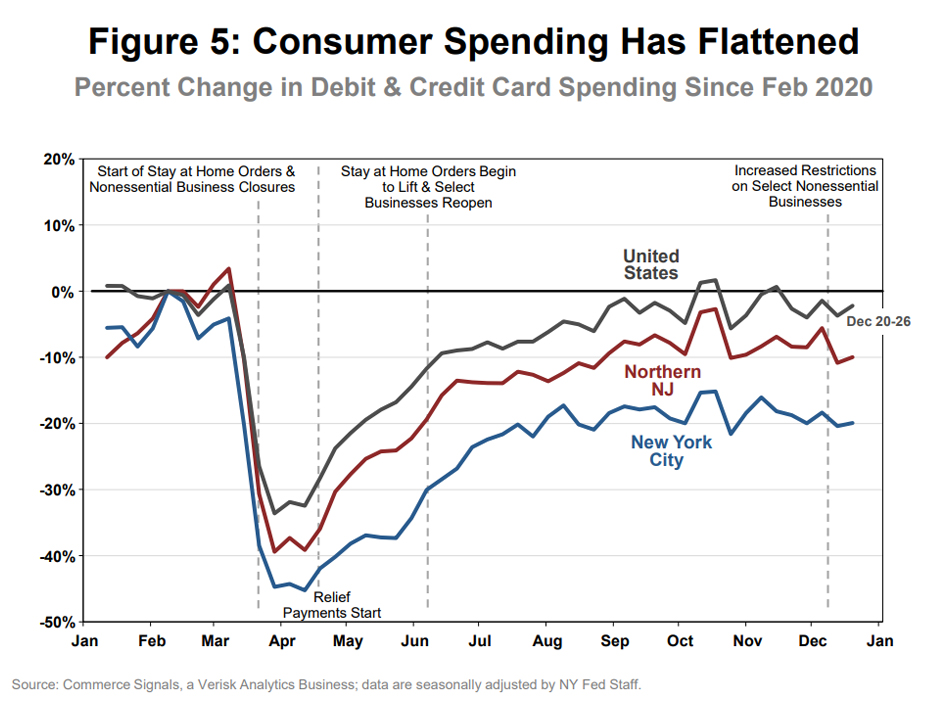

As the pandemic took hold, consumer spending plunged alongside business activity and employment, though it has since recovered to a large extent in many places. Figure 5 shows weekly consumer spending patterns, based on credit and debit cards. Looking at the United States first, spending declined by over 30 percent early in the pandemic. It then picked up, supported by the CARES Act, and essentially recovered to pre-pandemic levels, though it has flattened out more recently with the winter wave.

In New York City, the initial drop was sharper, as non-essential businesses were closed and people responded to the increased risks as the virus spread. Unlike the nation as a whole, spending never fully recovered even as restrictions were lifted, and it remains about 20 percent below pre-pandemic levels. Spending in Northern New Jersey followed a similar path, but has recovered more substantially.

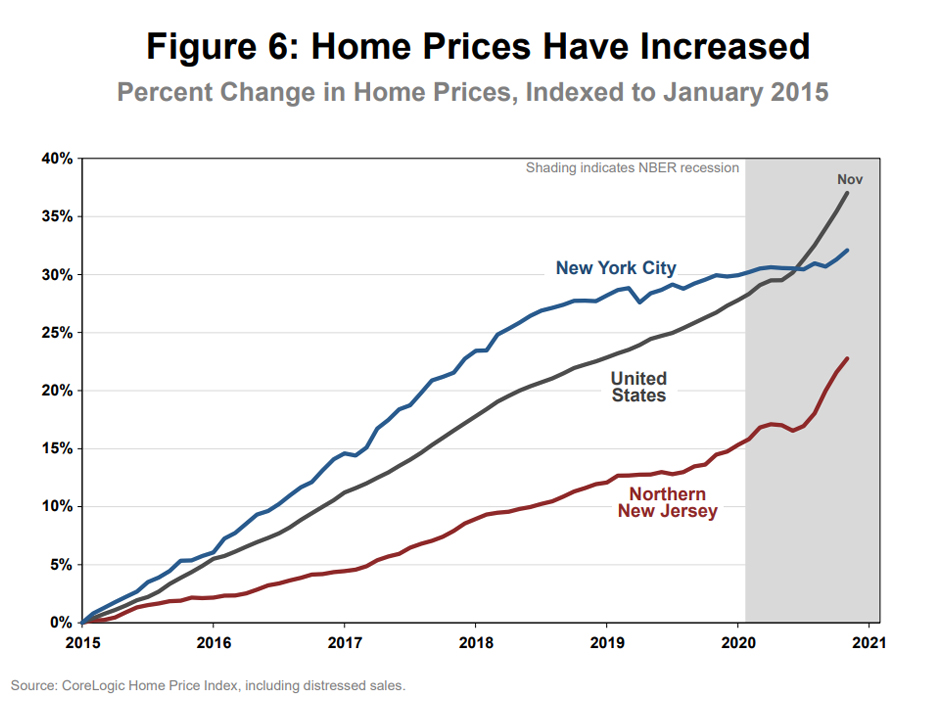

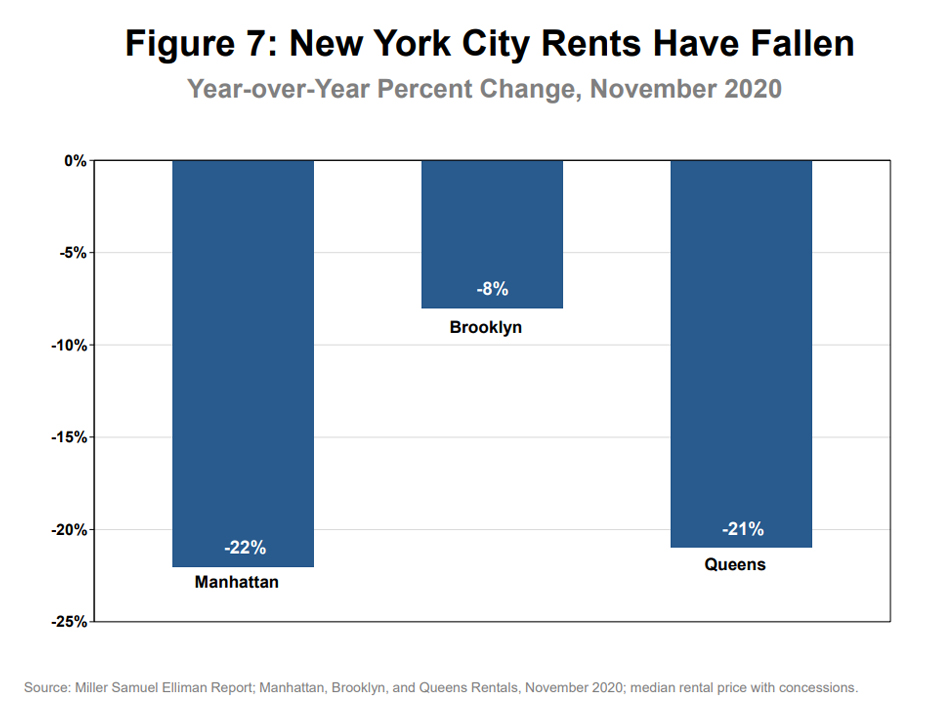

Despite ongoing weakness in the regional economy, housing markets have mostly held up well. In fact, as Figure 6 shows, home price appreciation has picked up in many places during the pandemic. This strength has been driven by a combination of historically low mortgage rates, lean inventories, and growing demand for home office space. However, the picture is a bit different in New York City, where home prices were flattening before the pandemic began and have not picked up as much as in other places since then. Moreover, as shown in Figure 7, the city's residential rental market has weakened sharply, in part because some people have taken the opportunity to work from remote locations, but also because the flow of people moving into the city has slowed.

The region's commercial real estate market has been much less buoyant than the residential market. We've seen rising vacancy rates and even some noteworthy declines in rents for office and retail space, especially in Manhattan. While New York City's key finance, information, and business service sectors have not sustained particularly steep job losses, many of these office workers have been working from home, reducing the need for office space. And, the drop-off in both tourists and business visitors has weighed heavily on hotels, restaurants, bars, and retailers throughout much of Manhattan.

Will New York City Ever Come Back?

So far, the picture I have painted is a gloomy one, and it calls into question the longer-term outlook for New York City. The mass exodus of office workers and tourists, along with the loss of some residents and fewer new people moving in than normal, has wreaked havoc on the local economy. And, with the city's key business sectors able to weather the pandemic by having staff work remotely, many have wondered: might this be the new normal? Now that we have learned to work from home, will businesses really need that much office space? Will dense cities and central business districts become a thing of the past? There are three reasons to be at least somewhat optimistic about New York City's future.

First, during the depths of economic crises like the one we are in now, it is difficult to maintain perspective on the ability of a region to recover from even the harshest of events. For example, after 9/11, many wondered whether people would ever feel safe in a skyscraper in New York City again. My New York Fed colleagues probed this question in the months after the attack by looking at real estate market signals.4 While rents across Lower Manhattan fell noticeably, home prices held up surprisingly well. This suggested that people ultimately had confidence in the business district's longer-term prospects. And, this signal turned out to be on the mark, as New York City, and especially Lower Manhattan, enjoyed an historic boom over the nearly two decades that followed.

Today, there are similar signals: rents have softened substantially, while selling prices have been much more resilient thus far.

Second, there are many advantages to working in cities, especially big cities such as New York, and these advantages are unlikely to disappear. Economic research shows that workers in big cities are more productive and earn higher wages than similar workers in other places.5 In part, this is because it is easier to share ideas and learn from one another when many people are living and working close together. Though many of us have come to rely on Zoom, it is hard to replace the informal face-to-face interaction that results in greater knowledge and higher productivity that is so important in today's economy.

Further, because of the volume and diversity of jobs in big cities, workers have a better opportunity to specialize in jobs that best match their skills, enhancing the productivity advantage. While remote work may create opportunities for some people to decouple where they live and work in the future, big cities are still where the most specialized and highly-skilled jobs will be located.

And third, big cities like New York offer residents a host of amenities, from Broadway theatres to neighborhood restaurants serving a wide variety of cuisines to numerous cultural attractions, all in close proximity. Once the pandemic has passed, and people feel safe again, many will once again seek out locations with easy access to such amenities.

All in all, the economic forces that were pushing us to live and work in big cities like New York were decades in the making, and I believe they will endure once we are past the worst of the pandemic. Thus, in my view, it is far too soon to conclude that New York City's best days are behind us.

Thank you for your kind attention.