Good afternoon. As members of the Foreign Exchange Committee, you are all well aware of the importance of well-functioning financial markets. I would like to thank you for the commitment you have shown to supporting the smooth functioning of the foreign exchange market. Your continued leadership is especially important in these challenging times. And we are all grateful to those who are putting themselves in harm’s way on the front lines to take care of others during this unprecedented public health emergency.

In early to mid-March, amid extreme volatility across financial markets triggered by the coronavirus pandemic, several markets at the center of the U.S. financial system were severely disrupted. In short-term funding markets, it was difficult to borrow for longer than overnight. In the usually very liquid markets for Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS), trading became impaired. In investment-grade credit markets, even healthy borrowers found that credit was unavailable or very expensive.

These markets matter not only for those who participate in them, but also—because of their central role in the financial system—for workers and families throughout the United States. Continued disruptions could quickly make it more difficult for families to obtain mortgages at reasonable interest rates, for businesses to fund their operations and pay their workers, and for local, state, and federal governments to pay for essential services. Such a credit crunch would exacerbate the hardships many are experiencing in this period of economic constraint necessary to fight the spread of the coronavirus, and reduce the odds of a strong recovery afterward.

Therefore, it was important for the Federal Reserve to act quickly and decisively to support market functioning and the flow of credit. Over a period of a few weeks, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target range for the federal funds rate to near zero. The Federal Reserve also announced a sequence of strong actions to support the flow of funding in short-term markets, the functioning of Treasury and MBS markets, and the availability of credit to households, businesses, and state and local governments.

Today, I will provide an overview of these actions to date from my perspective as manager of the System Open Market Account and head of the New York Fed’s Open Market Trading Desk. The Fed’s recent actions have involved an unprecedented array of tools—from standard open market operations conducted by the Desk and deployed on a larger scale than ever before, to new facilities that use the Federal Reserve’s emergency powers with the consent of the Treasury Secretary and financial backing from the Treasury and Congress. Some actions targeted problems in a single market, while others worked to support functioning across many markets. In addition, because they were deployed in close succession, the actions reinforced each other, with improvements in each market supporting the functioning of other markets and the financial system overall. I will speak about recent actions to support liquidity and the flow of credit in four areas: domestic short-term funding markets, international dollar funding markets, markets for Treasuries and MBS, and credit markets.

Before I proceed, let me note that the views I express are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System.1

Domestic Short-Term Funding Markets

Funding markets transfer funds from households and businesses that seek safe, easily accessible short-term investments to firms that have short-term borrowing needs. For example, a manufacturing company with a temporary surplus of cash might invest in a money market mutual fund, planning to take the money back out in a few weeks to invest in new equipment. In turn, the money market fund might buy commercial paper issued by another company that needs to cover its payroll, or it might use a repurchase agreement (or “repo”) to lend to a broker-dealer that needs to finance an inventory of Treasury securities. The smooth flow of funds in these markets allows businesses to readily finance their operations and investors to engage in vibrant trading that keeps a wide range of other markets working well.

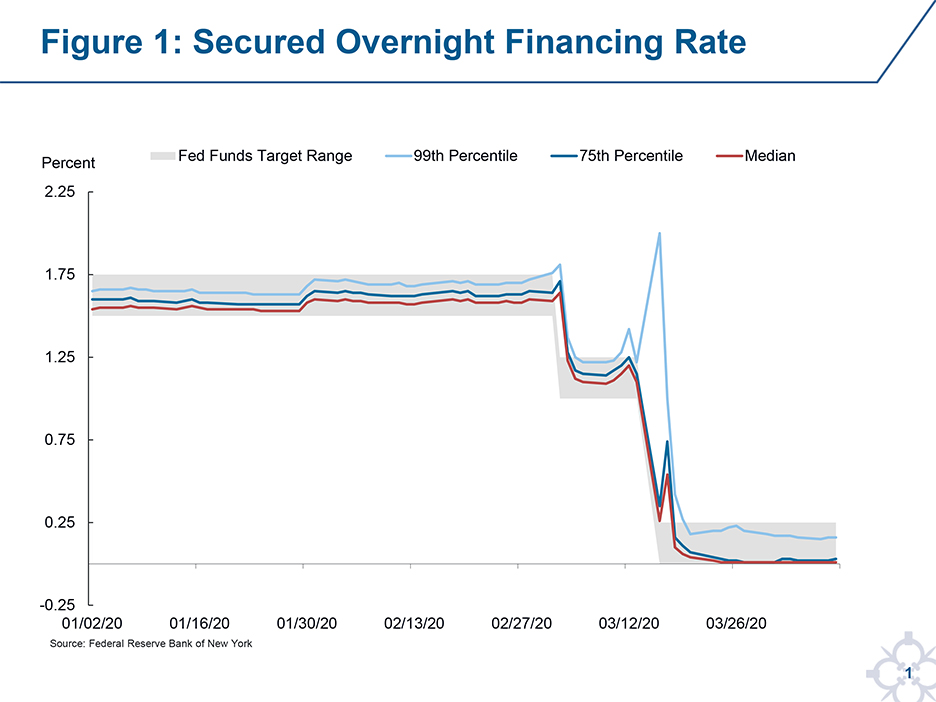

In mid-March, short-term funding markets became severely impaired. In repo and commercial paper markets, there was little term funding available. Even for overnight borrowing, some market participants paid much higher rates than usual. Figure 1 shows the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which is the median rate on certain overnight repos against Treasury collateral, as well as the 75th and 95th percentiles of the distribution of these Treasury repo rates. Ordinarily, this distribution of rates is very tight. However, in the second and third weeks of March, it widened notably, with some borrowers paying dozens of basis points above the median, and well above the FOMC’s target range for the federal funds rate.

The initial pressures in funding markets led to further strains. Investors became reluctant to buy the commercial paper of healthy issuers, for fear that when the paper came due, the issuers would have difficulty rolling it over into new paper. Prime money market funds—which invest in commercial paper—saw outflows of about $150 billion over the month of March as some investors worried that difficulty selling holdings would eventually prevent the funds from satisfying withdrawals.

Starting March 9, the Federal Reserve launched a series of actions to stabilize funding markets. The first two actions involved expanding the use of standard tools: repo operations by the Desk and discount window lending by all 12 Reserve Banks.

- The Desk increased daily offerings of overnight repos from $100 billion to $150 billion, then to $175 billion, and ultimately to even larger amounts.2 The Desk also began offerings of one-month and three-month term repos, each for $500 billion.3 These offerings allow dealers to access ample funding for Treasury and MBS collateral.

- The Federal Reserve Board lowered the primary credit rate by 150 basis points, to 0.25 percent, and announced that banks could borrow from the discount window for up to 90 days.4 These steps provide banks with ready access to funding that they can use to provide credit to households and businesses.

Shortly thereafter, several additional actions used emergency tools, based on the Board’s authority to act in unusual and exigent circumstances with consent of the Treasury Secretary and, in some cases, funding as well:

- The Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) allows the New York Fed’s primary dealers to obtain funding against a wide range of collateral at the same rate as the discount rate. By increasing dealers’ access to funding, this facility helps them to provide credit across numerous markets.5

- The Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF) lends against assets that banks acquire from money market funds. By helping to ensure that money market funds will be able to meet demands for redemptions, this facility encourages investors to leave cash in these funds, which then provide credit that flows to the broader economy.6

- The Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) purchases commercial paper directly from highly rated companies and municipal governments. The availability of this facility reduces the risk that eligible commercial paper issuers will be unable to roll over their debts at maturity. In turn, the reduction in risk encourages investors to buy commercial paper from businesses that use the funds to pay employees and invest in operations, and from municipalities that use credit to provide public services. Furthermore, because this facility purchases newly issued commercial paper, it not only enhances liquidity but also directly supports the flow of credit to eligible issuers.7

International Dollar Funding Markets

As the world’s preeminent reserve currency, the dollar plays a leading role in trade and investment far beyond our country’s borders. Banks around the world borrow dollars in international markets to finance these activities. In addition, global banks borrow dollars to finance investments in the United States—lending, that is, to American families, companies, and the U.S. government. As members of the FX Committee, you are well versed in the importance of international dollar funding markets.

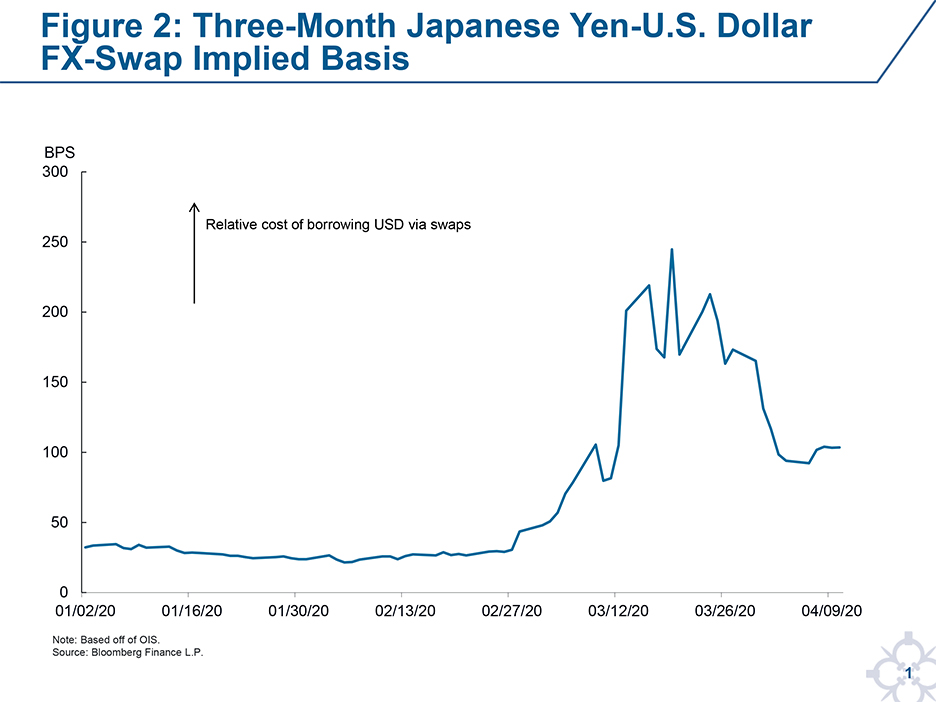

These markets, too, came under severe strain in March. Shown in Figure 2, the yen-dollar swap basis spread—a measure of the premium paid to borrow dollars using yen in the foreign exchange market—soared by roughly 200 basis points. Other foreign exchange swap basis spreads also rose sharply, and foreign exchange swap trading volumes declined. These pressures had the potential to spill over to domestic funding markets, as international banks can compete to borrow dollars in the U.S., as well as the potential to disrupt the flow of credit from international financial institutions to domestic borrowers.

To ease strains in global U.S. dollar funding markets, the Federal Reserve and other central banks took coordinated actions in March to enhance the provision of U.S. dollar liquidity through central bank swap lines around the world. These swap lines are designed to improve liquidity conditions in the United States and abroad by providing foreign central banks with the capacity to deliver dollar funding to institutions in their jurisdictions during times of global funding market stress. This supports activities that rely on access to U.S. dollar funding, including supplying credit to U.S. borrowers. The Federal Reserve and the central banks of Canada, the United Kingdom, Japan, Switzerland, and the euro area agreed to lower the pricing on the standing swap lines, to supply dollars at longer tenors in addition to regular one-week operations, and to increase the frequency of one-week operations. The Federal Reserve also established temporary swap lines, limited in size, with nine other central banks around the world.

In addition to the swap lines, the Federal Reserve established a temporary repo facility to allow foreign and international monetary authorities to temporarily exchange U.S. Treasury securities held in their accounts with the New York Fed for U.S. dollars. This facility provides those central banks with an alternative source of dollar funding that they can then lend to institutions in their jurisdictions. The facility also helps to support the smooth functioning of the market for U.S. Treasury securities by reducing foreign central banks’ need to sell these securities outright when private cash and repo markets become stressed.

Markets for Treasury and Mortgage-Backed Securities

The market for U.S. Treasury securities is commonly described as the deepest and most liquid in the world. Ordinarily, it is easy for investors to sell Treasuries quickly and at low cost. This liquidity adds significantly to the value of Treasury securities, helping the U.S. government to borrow at low interest rates. As many other interest rates are priced relative to the safe interest rate on Treasuries, the liquidity of the Treasury market ultimately reduces financing costs for families and firms throughout the economy.

Although not as liquid as the Treasury market, the market for agency MBS—pools of residential mortgages backed by Ginnie Mae, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac—is also ordinarily very liquid. This liquidity makes MBS a more attractive investment, supporting low mortgage rates and the flow of mortgage financing to American households.

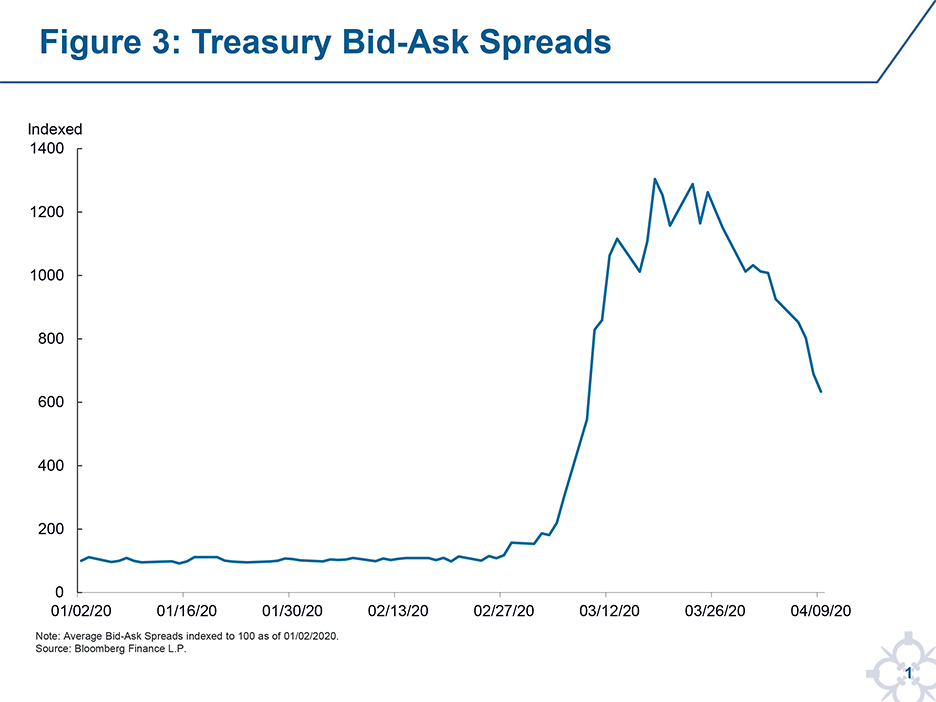

However, in mid-March, liquidity in Treasuries and MBS dried up. The Desk’s market monitoring and data analysis suggest that two key factors were at work. First, amid large moves in asset prices and uncertainty about access to liquidity, many investors sought to sell bond holdings. Some of these investors, such as asset managers that might need to meet redemptions, were seeking to raise cash. Others were rebalancing their portfolios after the sharp fall in equity prices, or exiting positions that were no longer viable in the highly volatile market conditions. These large sales of bonds drove up dealers’ inventories of Treasuries and MBS; facing balance sheet constraints and internal risk limits amid the elevated volatility, dealers had to cut back on intermediation. Second, volatile market conditions led some trading firms to step back from the market, further reducing liquidity. Figure 3 shows the consequences: The average bid-ask spread for Treasury securities, a measure of transactions costs, rose by a factor of about 13 over the first few weeks of March. Many other measures of functioning in the Treasury and MBS markets also deteriorated.

In response, the Desk, at the direction of the FOMC, is undertaking extensive purchases of Treasuries and MBS to support the functioning of these critical markets. Although asset purchases are a standard Desk tool, the scale of these purchases has been unparalleled, totaling about $1.6 trillion in the past four weeks. Also, we are now buying agency commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS), which are pools of mortgages on apartment buildings and other commercial properties that are backed by Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae. As important as the volume of purchases is the FOMC’s commitment, announced March 23, to purchase whatever amounts are needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy.8 Extending a strong commitment to support market functioning has calmed trading conditions and allayed the potentially self-fulfilling fear that conditions might deteriorate further.

I should note that supporting smooth market functioning does not mean restoring every aspect of market functioning to its level before the coronavirus crisis. Some aspects of liquidity—especially aspects related to transactions costs and market depth—are importantly affected by fundamental factors such as how the current extraordinary uncertainty about the economic outlook influences trading behavior. These aspects of market functioning may not return all the way to pre-crisis levels for some time, even as our purchases slow.

Nor does supporting smooth market functioning mean eliminating all volatility. In well-functioning markets, prices will respond rapidly and efficiently to new information. During the unprecedented disruption caused by the coronavirus pandemic, a great deal of new information arrives every day about the outlook for specific markets, such as housing, and for the economy as a whole. These changes in the outlook should move the Treasury and agency MBS markets irrespective of the Federal Reserve’s purchases.

Credit Markets

In normal times, credit markets allow households and businesses to finance a vast array of activities: buying a car or a house, attending college, covering a short-term gap between revenue and expenses, or making a long-term investment in new products or factories. In this time of economic stress, credit markets are all the more critical, helping families to borrow rather than forgo necessities, and helping businesses to keep going, cover their payrolls, and, eventually, make the investments needed for a strong recovery.

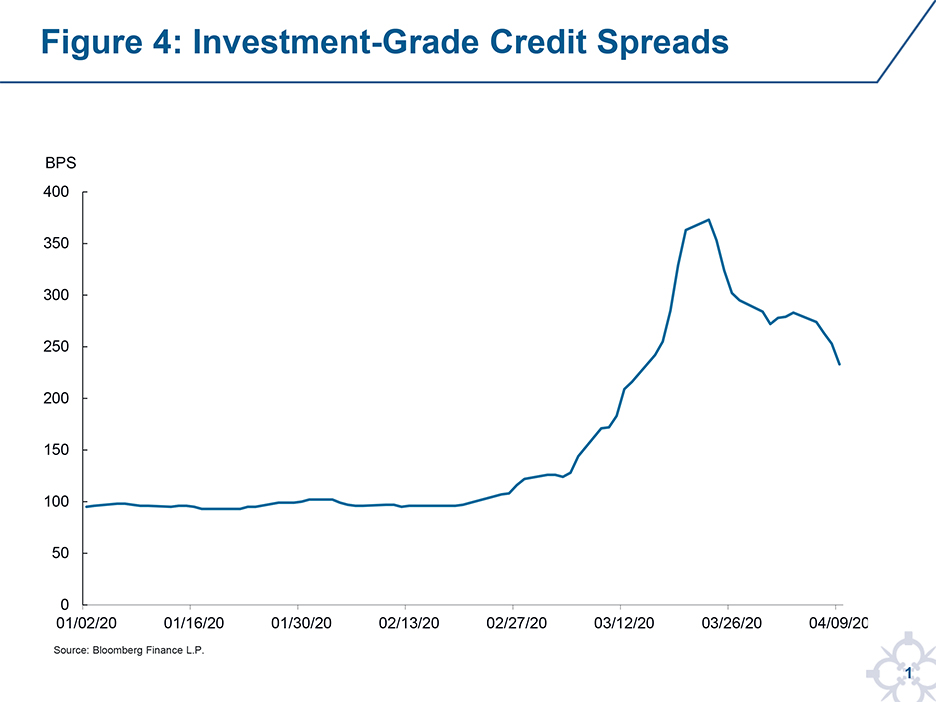

Yet credit markets have come under substantial pressure in recent weeks. For example, the spread of interest rates on investment-grade corporate bonds relative to Treasury securities widened by about 250 basis points from late February to mid-March, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Much of that pressure results from significant changes in the economic outlook: With many businesses temporarily closed and millions of people losing their jobs, lenders see a greater likelihood that some borrowers will be unable to repay. But impaired market functioning has also contributed to the pressures. For example, borrowers often repay their debts by borrowing anew, but rolling over debt is difficult in a stressed market, so lenders may conclude that market dysfunction will lead to defaults even by financially sound borrowers and respond by reducing lending or seeking higher interest rates. We saw several signs that poor market conditions were contributing to credit stress in March, including a drop-off in corporate and municipal bond issuance and large outflows from bond mutual funds.

Many of the Federal Reserve actions in funding and asset markets that I described earlier are also helping to support credit markets. For example, the PDCF, CPFF, and MMLF can all provide funding for loans to creditworthy borrowers such as households, businesses, or local governments, while MBS purchases support a key market for credit to households.

In addition, the Federal Reserve Board, with the consent of the Treasury Secretary and backing provided by the Treasury and Congress under the CARES Act, has used its emergency authority to announce numerous steps targeted at other major credit markets. The Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) will buy newly issued corporate bonds and syndicated loans, while the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) will give investors an outlet to sell corporate bonds—in both cases supporting a key market for credit to large employers.9 The Board has also announced a Main Street Lending Program that will purchase up to $600 billion in loans to small and midsize businesses, as well as a facility that will support the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) by supplying liquidity to financial institutions that make PPP loans to small businesses.10 In addition, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) will support the issuance of securities backed by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, small business loans, and other debt, while the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF) will lend up to $500 billion to state and local governments.11 All of these steps will help keep credit markets working and credit flowing to qualified borrowers in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Conclusion

Modern financial markets are closely connected to one another. Stresses in one market can easily lead to stresses in others, raising the risk that the financial system as a whole becomes significantly impaired. For example, if short-term funding markets are disrupted, otherwise creditworthy borrowers may have difficulty rolling over their debts—which can make the borrowers more risky and create pressures in credit markets. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-’08 showed how rapidly problems can spread across financial markets and ultimately damage the economy.

Today’s crisis is different, having originated outside the financial system, in an enormous challenge to public health. Yet the lesson of the previous crisis still applies, and the Federal Reserve has taken it to heart in responding to the recent stresses in funding markets, Treasury and MBS markets, and credit markets. By acting quickly and forcefully to support all of these markets at once, we have been able to stabilize market conditions. Many challenges surely lie ahead for the economy and financial markets. But the past month demonstrates that the Federal Reserve will use its tools aggressively to keep markets working so that credit can flow to households, businesses, and state and local governments throughout our economy.

Thank you.